By Giorgina Samira Paiella

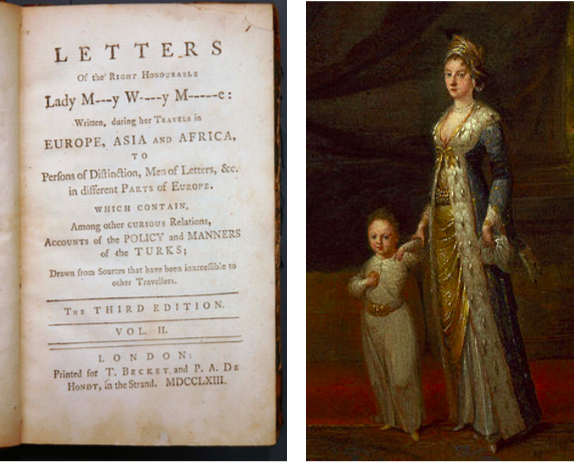

In 1724, Mary Astell wrote the following in what would later become the 1763 preface to Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s The Turkish Embassy Letters:

I confess, I am malicious enough to desire, that the world should see, to how much better purpose the LADIES travel than their LORDS; and that, whilst it is surfeited with Male- Travels, all in the same tone, and stuft with the same trifles; a lady has the skill to strike out a new path, and to embellish a worn-out subject, with a variety of fresh and elegant entertainment. [1]

Montagu’s travel writings were groundbreaking not only because they were the first letters written by an English woman about her travels in the (then) Ottoman Empire, but also because— as Astell notes—travel writing at large was coded as a masculine genre dominated by male narratives.

What did it mean for Montagu to “strike out a new path,” not only in the travel writing genre, but also from her unique subject position? Montagu’s identity was a layered and complex one—though certainly a minoritized female voice in the overwhelmingly male travel writing genre, she also had unique privileges as a white British subject and wife of the British ambassador to Turkey, Edward Wortley Montagu, with whom she traveled from 1716-1718 as part of his position intended to keep trade running smoothly and foster a truce between warring nations, a goal that was ultimately unfulfilled. But there were also unconventional aspects to her journey and character. Montagu traveled with her young son and later gave birth to her daughter while abroad. She inoculated her young son against smallpox according to the technique she observed during her travels and later advocated for the method once she returned to England, which was unfamiliar to Western medicine and therefore controversial at the time. [2] Her letters are never entirely devoid of moments when the hegemonic gaze and European biases enter, though Montagu also reveals in her letters a keen interest in the Turkish language, cultural customs, respect for medical and technological innovations, and attempts to dismantle the widespread assumption that “these people are not so unpolished as we represent them,” as she states in letter 44 to the Abbé Conti. [3] She also notes the unexpected freedom enjoyed by women and the spaces that they were afforded for socializing, conversation, and bonding that were not available to women back in England, though it bears noting that class isn’t often factored into Montagu’s own assessment of cultural norms, and these spaces—as well as greater freedom of mobility—were primarily available to upper-class women. Montagu hones in on the hammam in particular, which she calls in her letters “the woman’s coffee house.” [4] And Montagu herself was very aware of the new paths that she was carving out for gender, genre, and authorship as the first British woman to write accounts of her travels to the Ottoman Empire—as scholars have widely noted, despite the ostensibly private nature of her correspondences, Montagu always had her eye toward publication of her letters as she was writing them, which were eventually published posthumously in 1763.

I detail here the work that I’ve conducted to map and visualize Montagu’s Turkish Embassy Letters with digital humanities (DH) tools. I examine Montagu as a literal and figurative worldmaker, not just in offering a glimpse of a world that had not yet been seen through the lens of a British eighteenth-century female aristocrat, but also calling attention to the ways in which the writer and traveler is always engaged in fictional world building—regardless of how faithful the glimpse into a culture is, and even if the narrative enterprise is one that attempts fidelity to real events and details. I examine the affordances but also the challenges that emerge when building a DH visualization of Montagu’s letters—which are some of the same issues that arise in The Turkish Embassy Letters themselves— teasing out resonances that link the eighteenth century, DH methodology, the epistolary genre, and both literary and digital worldmaking.

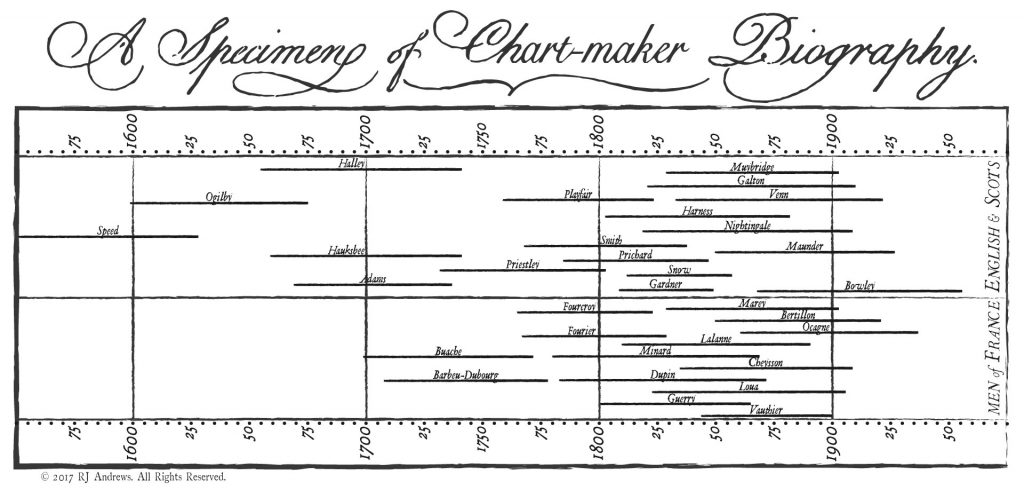

To begin with the building blocks of the project and the starting premise of visualization, what does visualization do for us? In short, visualization reveals. Data viz has a long history, and humans have used visualization to categorize things in the world and understand them in both real and fictional worlds.

Many DH outputs rework traditional, familiar visualizations. While not all of us are intimate with DH, for example, we are familiar with the map, the timeline, the graph, tree diagrams, and more—borrowed from disciplines as far-reaching as geography, data science, biology, and history. While DH often makes these more interactive, the underlying impulse is the same—to organize data beautifully and to reveal patterns, emergent qualities and trends, and open the door to new kinds of narratives in what isn’t immediately apparent or visible.

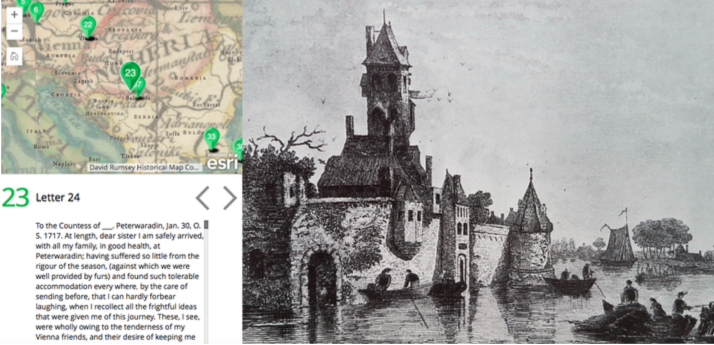

Montagu’s letters are particularly well suited to mapping and visualization. Her letters from various locales that she visits on her travels not only allows for a mapping of her route during her journey, but her descriptions are vivid and abundant with imagery. I created an interface where her letters can appear alongside period-specific images of landmarks, people, and places that Montagu encountered during her travels as an educational tool, and also because producing imagery of these lands is an important way to demystify both written and visual representations that are still dominated by Western renderings.

Click here to view the project interface in full. Additional image citation information is available here.

Data viz always comes with challenges, but there are also unique challenges that face eighteenth-century DH tool and interface building at large. I discuss here three broad categories of challenges that arose while I worked on this project.

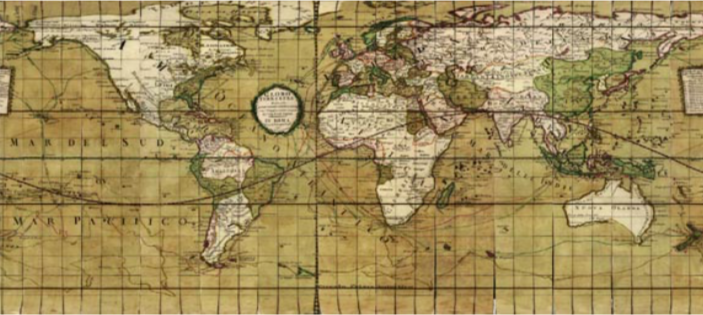

Maps, Borders, and Boundaries

The first set of challenges involves maps, borders, and boundaries. I worked with ArcGIS technology to allow for interactive map work. The long eighteenth century was an important era for cartography as colonial empires continued to expand and new territories were acquired. The need to visualize these new territories was in itself an act of world making—of redrawing borders and claiming them for a given country or empire. These entangled issues of territory, borders, and empire led Foucault to fittingly refer to the map as an instrument of “power/ knowledge”. [5] No map—be it paper or digital—is neutral, but rather a complex entanglement of power and positionality.

To build a map for this project, I grappled with how to reconcile historical maps with present-day maps—while I wanted to maintain fidelity of the land as Montagu herself would have encountered it, I also wanted to place her travels in the context of current territories to visualize how these borders shifted over time. I overlaid a historical map with a current-day one to allow entrypoints into both worlds, then layering on the stops along her tour as dropped pins.

Another issue pertaining to borders and boundaries is the issue of how certain cities are identified in Montagu’s letters. The discrepancy between the historical names for given cities and countries and their current names required inputting geolocation information for the modern-day counterparts to the cities Montagu mentions—Edirne for Adrianople, Istanbul for Constantinople, Peterwardein, now Petrovaradin, one of the two municipalities that comprises the Serbian city of Novi Sad. She recalls in one letter, that the inhabitants of Peterwardein were “weary of the war.” [6] Montagu often provides insights in her letters not just into lifestyle and customs of a given locale, but also into conflicts affecting the citizens of the countries and territories she was visiting, lending an ethnographic quality to her letters that can accompany representations of the geographic landscape.

Imagery

The second category of challenges revolves around imagery. Montagu’s letters, of course, were solely produced in written form, though the ethnographic detail imbued in her writings and attention to detail pertaining to architecture, customs, and encounters almost calls out for some type of visualization. Most DH viz projects utilize modern maps and photographs. The eighteenth century, of course, predates the photographic era, so I relied primarily on paintings, sketches, and engravings to stay faithful to the time in which Montagu was writing, occasionally including later illustrations and more modern simulations if eighteenth-century images were not available. Two other facets of challenges relating to imagery are access and availability. While it was not difficult to find appropriate images for the first few European stops on Montagu’s journey, there was a drastic drop in the number of viable images once Montagu gets to modern-day Serbia.

It became increasingly difficult to find viable images of historical landmarks and cultural traditions as Montagu’s travels progressed in the Ottoman Empire—one prominent example was the absence of available images of the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne (then Adrianople). Viable images also became increasingly orientalist as distance from Europe increased. One prominent example is the abundance of European harem paintings of Turkey and other Middle Eastern locales and the overall skew toward sexualized female portrayals. Archives and databases, too, have never been neutral.

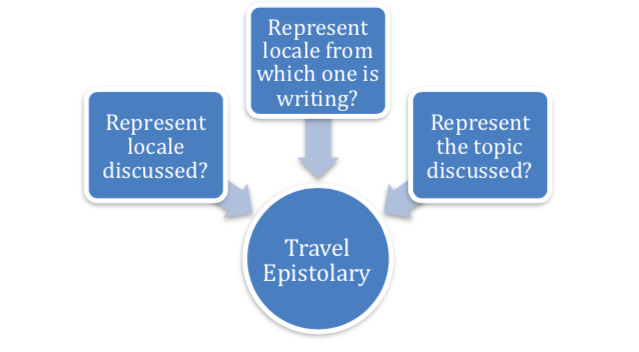

A final question that arises with this viz project in relation to imagery—and which I argue is unique to the travel epistolary in particular—is how to make decisions about what is visually represented. It is very common for Montagu to reflect upon a given locale and her experiences there from her next destination in her letters—Montagu is in Lyons, France, for example, when she is discussing her journey from Turin, Italy. Should images selected represent the locale Montagu discusses in her letter, the place from where she is writing, or the topic discussed? Though I made these choices based on viable images and what occupied Montagu’s attention in a given letter, these complexly layered questions about representation remain pressing to the travel epistolary genre.

Perspective and Vantage Point

A final category of considerations—one that is symbiotic with that of images and imagery—is about perspective. It often seems as though DH projects are build from an omniscient vantage point, but like all tools and platforms, DH projects are always built from a given standpoint. Like any artifact, we need to consider who builds a DH project and the perspective through which that project is built, as well as what the project represents and through what perspective. This issue recalls one of the most famous letters in The Turkish Embassy Letters—the bathhouse letter. Montagu looks upon all of the naked women in the hammam while she is still outfitted in her stays, an outsider looking in. She states:

To tell you the truth, I had wickedness enough, to wish secretly, that Mr. Gervase could have been there invisible. I fancy it would have very much improved his art, to see so many fine women naked, in different postures, some in conversation, some working, others drinking coffee or sherbet, and many negligently lying on their cushions, while their slaves (generally pretty girls of seventeen or eighteen) were employed in braiding their hair in several pretty manners. [7]

Montagu thinks of the painter Charles Jervas, and in this moment, perspectives are complexly collapsed and layered—Montagu is watching the women in the bathhouse, mediating what she is seeing through the perspective of the absent male artist. From whose vantage point are things being seen, viewed, and experienced?

In addition to these fascinating moments in the text, Montagu herself acknowledges that her interaction with these locations and environments is in flux. In her letters from Genoa in 1718, at the end of her travels, she writes to Lady Mar, “The church of the annunciation is finely lined with marble; the pillars are of red and white marble; that of St Ambrose has been very much adorned by the Jesuits; but I confess, all the churches appeared so mean to me, after that of Sancta Sophia, I can hardly do them the honour of writing down their names”. [8] And in another letter from Genoa, “The churches are handsome, and so is the king’s palace; but I have lately seen such perfection of architecture, I did not give much of my attention to these pieces.” [9]

In her letters, Montagu crosses different thresholds and the manner in which she interacts with her environment is constantly changing, evolving, and being revised. The letters—and Montagu’s experiences at large—are interactive, and shaped by traveler, writer, and place. In Letter 27 from Adrianople on April 1, 1717, Montagu writes, “I am now got into a new world, where every thing I see appears to me a change of scene.” [10] Montagu’s travel epistolary world making and digital world making seem more connected than ever, both crossing over and representing different thresholds of experiences.

Notes

[1] “Preface by a Lady” (Montagu 221).

[2] See Letter 32 from Montagu to Mrs. S.C. (Adrianople, April 1, 1717).

[3] Montagu 179

[4] Montagu writes, “In short, ‘tis the woman’s coffee-house, where all the news of the Town is told, scandal invented, etc.” (Montagu 102).

[5] Foucault asserts the map is an instrument of power-knowledge in The Order of Things, An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (1966) and The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language (1969).

[6] Montagu 96

[7] Montagu 102

[8] Montagu 198

[9] Montagu 199

[10] Montagu 100

Works Cited

Montagu, Lady Mary Wortley. The Turkish Embassy Letters. Edited by Teresa Heffernan and Daniel O’Quinn. Broadview, 2012.

Interface Image Credits

Note: Montagu’s letter-book jumps directly from Letter 21 to Letter 23 and are numbered in the interface and in these image credits accordingly.

Letter 1st

Rotterdam Binnenrotte. Boeranvismarkt (voorgrond) Gravure Leon Schenk, 1750

Letter 2nd

“The Hague – International City of Music in the 18th Century” Walking Tour and App

https://i.ytimg.com/vi/tIoIiUUr5ZE/maxresdefault.jpg

Letter 3rd

“View from North-West to the castle Valkhof in Nijmegen” by Jan van Goyen (1641)

https://arthive.com/res/media/img/oy800/work/239/445373.jpg

Letter 4th

“Der Heumarkt um 1700 – Köln im Wandel der Zeit”

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/36/Der_Heumarkt_um_1700_-_Köln.jpg

Letter 5th

Nuremberg, The Liber chronicarum

Letter 6th

“Vienna, Eighteenth Century. Vienna, behind ramparts, seen from Leopoldstadt, the suburb on an island in the Danube. Line engraving, Austrian, mid-18th century.”

https://images.fineartamerica.com/images-medium-large/vienna-18th-century-granger.jpg

Letter 7th

Johann Ziegler n janscha 1792 redoute

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e0/Ziegler_n_janscha_1792_redoute.jpg

Letter 8th

The Imperial Opera House, Vienna

https://viennachoralsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/pannini.jpg

Letter 9th

Eighteenth Century Women’s Hoop Petticoat

https://daily.jstor.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/hoop_skirt_18th_century_1050x700.jpg

Letter 10th

St Michael Wing of The Hofburg

https://www.hofburg-wien.at/fileadmin/_processed_/4/c/csm_aaaaaaaaa_36727cea32.jpg

Letter 11

St. Michael’s Square, Vienna

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/25/e6/7a/25e67a5e2bf973201e2197eae669a33d.jpg

Letter 12

“View of Vienna from Belvedere” by Bernardo Bellotto (1781)

Letter 13

Vienna Coal Market, Austria, 18th Century, by Carl Schutz (1786)

https://www.mediastorehouse.com/p/617/austria-vienna-kohlmarkt-color-print-9571071.jpg

Letter 14th

The Citadel Of Prague, Czech Republic, 18th Century

Letter 15

“Auerbachs Hof in Leipzig” (1780)

Letter 16

Braunschweiger Schloss (Brunswick Palace), Built between 1717-1791.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/af/Braunschweig_Brunswick_Korb-Schloss_vor_1830.jpg

Letter 17th

Herrenhausen Gardens, Hanover (c. 1708)

Letter 18

Portrait of Wilhelmine Amalia of Brunswick-Lüneburg (c. 1700)

Letter 19

Blankenburg Castle off the Coast of Flanders by Charles Brooking

Letter 20

Theater am Kärntnertor, Vienna

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/bb/Karl_Wenzel_Zajicek_Kärtnertortheater.jpg

Letter 21

View of Dresden from the right bank of the Elbe with the Augustus-Bridge by Bernardo Bellotto (1748)

Letter 23

Michaelertrakt, Vienna

https://www.hofburg-wien.at/fileadmin/_processed_/4/c/csm_aaaaaaaaa_36727cea32.jpg

Letter 24

Petrovaradin fortress

Letter 25

Siege of Belgrade engraving (1717)

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e4/Belagerung_belgrad_1717.jpg

Letter 26

“Sofia” by Felix Kanitz

Letter 27

“The Great Bath of Bursa” by Jean-Léon Gérôme

https://eluxemagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/painting.jpg13-e1381196485562.jpg

Letter 28

A Street in the Suburbs of Adrianople

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/8c/e6/0e/8ce60e9ce32c03c89bf5c4275a3ef05e.jpg

Letter 29

“Madame de Pompadour at Embroidery” by Carle Charles-André van Loo (1747)

https://qph.fs.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-98370f63ddf4621a77a6bf9c5863ed87-c

Letter 30

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, hand-colored lithograph by by Achille Devéria, printed by François Le Villain, published by Edward Bull, published by Edward Churton, after Christian Friedrich Zincke

Letter 31

Old Ottoman Turkic Script

Letter 32

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu with her son, Edward Wortley Montagu, and attendants, attributed to Jean Baptiste Vanmour (c. 1717)

Letter 33

The Audience of the Grand Signor (A Sultan of Turkey receiving a British Ambassador), c. 1755-1765

Letter 34

“Enjoying Coffee,” Pera Museum, Istanbul.

https://i.pinimg.com/736x/11/d4/f6/11d4f6bfe8eb059208737c880ac329f6–french-school-turkish-coffee.jpg

Letter 35

Selim III, detail from the “Reception at the Court of Selim III at the Topkapi Palace,” gouache on paper. Turkey, 18th century.

Letter 36

“Entrance to the Port of Constantinople” by Clara (or Chiara) Mayer (née Barthold) (c.1794)

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/1f/b7/8a/1fb78ad963d20aa5a8b0a95544626d0e.jpg

Letter 37

Belgrade, Serbia, 1700s.

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/C277Bp_XUAAK-6P.jpg

Letter 38

“View of Belgrade, Serbia.”

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/C51kDj2WgAYKDh1.jpg

Letter 39

A View of Constantinople, from plate 5 of Antoine Melling’s Voyage pittoresque de Constantinople et des rives du Bosphore

Letter 40

Panoramic View of Istanbul, late 18thcentury

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/C7v_q7fXUAEuwlu.jpg

Letter 41

Panorama of Istanbul by Antoine de Favray (1773)

https://turkceden.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/858030_2159963838904_545279425_o.jpg

Letter 42

The Hagia Sophia

Letter 43

“Wedding Procession on the Bosphorus” by Jean Baptiste Vanmour (c. 1720-c. 1737)

https://www.pictorem.com/uploads/gallerysmall/gallerysmall_29814.jpg

Letter 44

“The Ottoman Palace” by Adrien Dauzats

Letter 45th

“Ruines de Stratonicée” byMarie-Gabriel-Florent-Auguste de Choiseul-Gouffier (1782)

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/DBvyqV4XkAEj7Kq.jpg

Letter 46th

Perspective view of Genoa, 18thcentury

https://assets.catawiki.nl/assets/2017/2/16/4/3/9/43907a80-f44f-11e6-8b92-29fc72cac1be.jpg

Letter 47

Castello Valentino, Turin, engraving from the album Theatrum statuum regiae celsitudinis Sabaudiae ducis (1682)

Letter 48

Banks of the Saône river in Lyon in the 18thcentury

https://www.goodfreephotos.com/albums/france/lyon/lyon-in-the-18th-century.jpg

Letter 49

Claudius, Speech to the Senate, from Lugdunum (Lyons) (48 CE)

https://cmuntz.hosted.uark.edu/_Media/the-lyons-tablet—speech_med_hr.jpeg

Letter 50

Château de Fontainebleau, 18thcentury

Letter 51

“Raguenet Vue de l’Ile de la Cité avec le Pont Neuf et la pompe de la Samaritaine” by Jean Baptiste Nicolas Raguenet (1752)

https://s01.sgp1.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/article/105804-shyshswgls-1542362775.jpeg

Letter 52

Castle Hill and Dover Castle

https://doveruk.s3.amazonaws.com/archive/960/151-dover-castle-kent-by-thomas-whitcombe.jpg

Letter 53

“Dover Castle, Kent” by Thomas Whitcombe (1808)

https://doveruk.s3.amazonaws.com/archive/960/151-dover-castle-kent-by-thomas-whitcombe.jpg